Words are important. They have weight. They craft and mould and create. Consider the sentence: “I never said she stole my money.” Put an emphasis on each word, and the sentence has seven different meanings.

- I never said she stole my money. – Translation: not me, buddy.

- I never said she stole my money. – Translation: I didn’t say that.

- I never said she stole my money. – Translation: But maybe I implied it?

And on and on and on.

Why is that important?

Because I want you to look at the definition of native advertising with the knowledge that syntax and emphasis matters.

And here it is: Native advertising, noun: a form of paid media where the ad experience follows the natural form and function of the user experience in which it is placed.

That definition comes via Sharethrough, a modern ad platform dealing entirely in native advertising. It’s one I like because it gives substance to the ‘native’ part of the definition that seems so alien to many marketers. It’s native not because it belongs or originates on a given blog or platform, but because it takes the form of the given platform. (Usually.)

I actually prefer the term advertorial (from the old school print publishing realm), though marketers also use any of: sponsored content, branded content, native content, and native advertising. They're often interchangeable.

Words. Aren't they great?

But let’s move away from the nitty-gritties of definitions

Strategic content marketing exists to catch people at a specific point in a journey. They have a problem and they need to solve it. Your content exists to solve it. Regardless of your KPIs, the end result is the same.

Sometime in the near or far future a person will think of your brand because they read your blog or saw your ad campaign or clicked on your PPC ads. Brand awareness isn’t a measure of immediate success. There is life beyond the now—beyond the immediate.

But that’s not to say all content has to be so focused. Some of it can be silly or smart or straight-up absurd. In the heart of the ridiculous is the sublime, right?

So where does native advertising come into play? And is native an element of content marketing? Or is it a separate thing and just advertising dressed up all fancy?

Is native advertising content marketing?

Content marketing is all about strategically aligning content to business objectives. It’s about personas and strategy. Otherwise, you’re creating all of the things and shooting them into the ether. Dumping noise on noise on noise. Native advertising is advertising in the realm of digital. It can be strategically aligned and about personas.

BUT, and it's a big but, native advertising is not content marketing.

However, native advertising is a strategy piece and content marketing tactic. It's just as viable a tactic as a social campaign or a blogging sprint or a well-timed video launched into the world.

Because here's the thing: native advertising done right can be an easy win for a client. Match a big brand with relevant content and you’ll rake in reaction, traffic, and, hopefully, leads. But not everyone is convinced--and that's where the quarrel lies.

Plenty of marketing types see native advertising as akin to product placement. Think of any of your favourite films. In Wayne’s World, Wayne and Garth eat pizza from Pizza Hut. James Bond drives an Aston Martin and sips a Heineken. E.T. snacks on Reese’s Pieces. (Fun fact: in my memory, I swore for years that E.T. ate M&Ms. He doesn’t as Mars rejected Spielberg’s request to use M&Ms. Also five-year-old me had no idea that Reese's Pieces were a thing.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AfAzUAxWELU

The list of famous product placement goes on.

We see these brands and we remember them. Sometimes it’s subtle. Sometimes it’s not. The bad happens when a character turns to the screen to extoll the virtue of the product and it moves from placement to pitch. In many ways, native advertising is the product placement of the content world.

It can be bad. It can be good. It can be a disaster, where your favourite brand suddenly starts talking about a random product in the middle of a seemingly normal article on a site you frequent. I think it's time for examples. First up, let's look at what happened when Cadbury teamed up with DailyEdge.ie. One of their first advertorials starts with the following text:

MARTHA PLIMPTON ONCE said that she felt comfortable in the presence of oddity.

“Probably,” she added, “because I’m a bit odd myself.”

Well, we’re all comfortable in the presence of oddity here at DailyEdge.ie Towers – and we’ll leave you to draw your own conclusions about the rest.

Everything about this suggests that the article is a true native piece and not the false-native scope of an advertorial. Here, the good people of the DailyEdge will talk you through weird crap that happened in the news. The article goes on to discuss a cat-sized rat caught in a Dublin home, an Indian man who eats bricks, and the possible nuptials of Ireland’s gay penguins.

What does that have to do with Cadbury’s chocolate? Down the end of the article is the following text:

This article was brought to you by Cadbury.

Well, that was unexpected. Still in the mood for more unusual antics? Try Cadbury Dairy Milk combined with Lu and Ritz crackers, unexpected but delicious. Available in shops now. #FreeTheJoy

Note the tagline: unexpected but delicious. What, in the quoted examples from the article, meets that quota? Yum cat-sized rats. Nomnomnom gay penguins.

And therein lies the issue so many people have with native advertising:

- They have no idea they’re being advertised to until a bait and switch at the end.

- The link is a stretch, or tenuous at best.

- It feels cheap or irrelevant and not earned.

The article drew 16,000 views--which is great. However, on a cold-ish Friday in Dublin, having read that article I now really want a Creme Egg. I might pick one up on the way home.

Incidental brand awareness leads to a conversion. Job done.

(Don’t worry, there is no unexpected twist here: this article most certainly isn’t sponsored by Cadbury’s. If they want in however…holla?)

The Irish Independent (henceforth called the Indo) has a more sartorial approach to native advertising with an entire section of sponsored brand content from a wide variety of brands like LIDL, Specsavers, and Bord Bía.

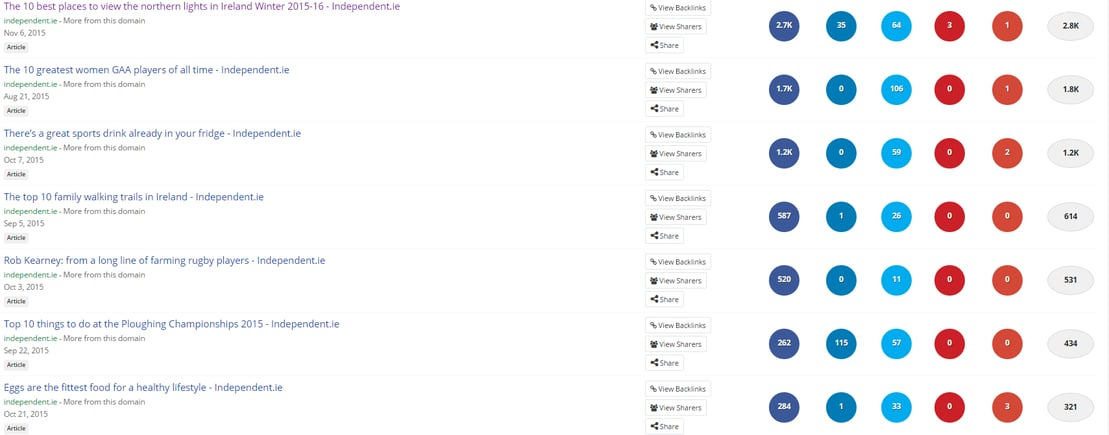

And how does that native content do? Solidly, by all accounts. Per Buzzsumo, the 7 most shared articles on the /storyplus domain are:

What does that tells us?

- Consumers are down with advertorials as long as they feel natural and make sense. The majority of these articles are exactly what they claim to be, as opposed to Cadbury’s advertorial in the DailyEdge that’s an advert masquerading as a story about a chicken who really did cross the road.

- Listicles forever. The listicle remains an indelible and click-worthy part of online media.

- Advertorials work better when they play to a reader’s expectation and intelligence. Don’t pretend an advert isn’t an advert.

- Advertorials can work—but they’re not nearly as likely to blow up. Compare these seven articles to the seven most popular articles on the Indo domain, and there’s no comparison. So while people will embrace native content, it’s not on nearly as wide a scale.

- The ads can take several different forms. Some are very obviously ads. Others take the form of regular content. Let’s look at two examples from the Indo again:

Exhibit a:

Big brands like Audi have paid big bucks to advertise on the Indo. However, while billed as such, I would say this strays from native advertising to straight-up advertising. This content is a completely different form to regular Indo content and may have been part of a larger brand takeover.

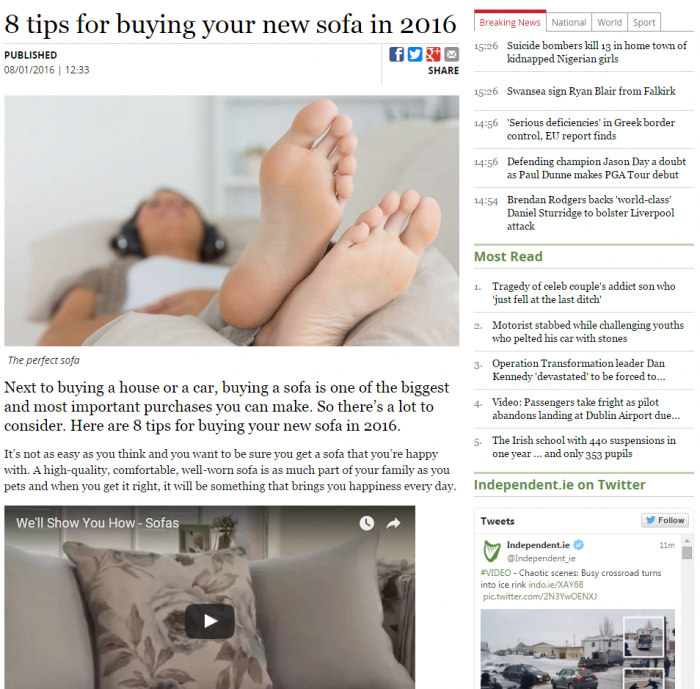

Exhibit b:

Here, Harvey Norman are pimping their sofa range. Sofa so good, right? (I’m sorry.) This is more in-line with what native is/should be: a straight article that is exactly what it says on the tin, though again it does lean very heavily on the advertising side of things as every single one of the eight points has the end-goal of sell.

That said, it does actually pass as a piece of content people might want to consume, whereas—pretty as it is—the Audi content is very much an ad. That's how the Indo does it, but how do Irish online publishers get on? The realm of online publishers certainly gets murkier.

Exhibit 2a:

I found this piece by Googling 'her.ie sponsored content'. It's the second part in a two-part series, revealing the results of a survey Her ran with JustEat. Nowhere in the post does the copy indicate it's an ad--and *cough* maybe *cough* it isn't--but Her might want to add a 'sponsored by' tag if they'd like to keep in line with ASAI standards.

Takeaway (weh weh weh):

- Tag your content as sponsored, folks.

- Irish people don't like sushi.

- The advertorial got 22 shares, so didn't exactly light up the interwebs.

Exhibit 2b:

In another team-up with JustEat, banter-merchants Waterford Whispers took more than a couple of potshots at Lovin' Dublin in their satirical article about a pizza that changed the writer's life.

With 350 likes on Facebook, the reaction was pretty good, though it did generate comments from readers who weren't so chuffed with the content. Again, while we can infer this piece was sponsored by JustEat, it's lacking clarity. While that would have flown in September when the piece was published, it's a no-go now.

Native ads, a manifesto on moving forward

The very interesting thing about native ads is how they’re evolving. They’re almost an outlier in many ways, often an ad pretending not to be an ad. But let’s step away from the Irish media scene and consider the broader implication.

Look at Snapchat as a native advertiser/publisher. Look at Facebook’s Instant Articles or LinkedIn Pulse. Is this native content or outreach or something else? 21% of BuzzFeed’s traffic comes from Snapchat—or certainly it did in September 2015. BuzzFeed’s content on Snapchat meets the definition of native advertising quoted at the top of this article, as it's native to Snapchat and is essentially an ad. And there's absolutely nothing wrong with that; it's clearly an important part of their strategy.

LinkedIn Pulse articles could be considered native advertising too, as many of the articles there are often reasonably authentic content meant to bring the reader to a product or webinar or something else.

Facebook’s Instant Articles belong to a whole new category entirely as they don’t follow the native form/function of Facebook itself--though the definition might evolve again to include them.

And therein lies some of the confusion. Digital is ever-evolving. Definitions can’t be stagnant or they won’t keep up. Native advertising or advertorials or branded content means something different to many different marketers. Marketers make moulds to break them.

However, a couple of things are certain:

- Native advertising is not the same as content marketing, though it can be a viable part of a strategy if utilised correctly.

- Do it wrong, and it may tank. Inversely, do it right and it can work well.

- The ASAI and other ad authorities are slamming down on content that’s pretending not to be ads, so bloggers in particular need to start properly labeling content as sponsored. A lot of the malaise around native advertising is that it’s not often obvious that you’re about to be advertised to. People very obviously value value but also transparency.

- With adblocking software having such a firm foothold, native advertising is an opportunity to move away from the dusty realms of obnoxious site takeovers and banner ads. (Like seriously, up to 50% of mobile clicks on banner ads are accidental. I do it all the time and I don't even have fat fingers.)

What we’re currently calling native advertising or advertorials may well get a rebrand in a year or two. We absolutely need to talk about native advertising, but it’s not a conversation that begins and ends in 2016. It’ll keep going and growing and that’s where the true conversation lies.

Lisa Sills

Previous Post

Is Brand Storytelling just 'Bullshit Bingo' on steroids?

Next Post

The great content dilemma: What should I be doing?

Subscribe Here

You may also like...

Nicole Thomsen | Dec 11, 2023

Nicole Thomsen | Nov 6, 2023

Nadia Reckmann | Nov 2, 2023